Lots of people know that Chile is a very long country and one way of understanding this is to unfold a standard size country road map. Most countries fit fairly nicely onto the map, or can be put easily onto two sides – not so Chile. When you unfold the map for Chile you find it consists of a series of long, thin slices which take a little while to get your head around.

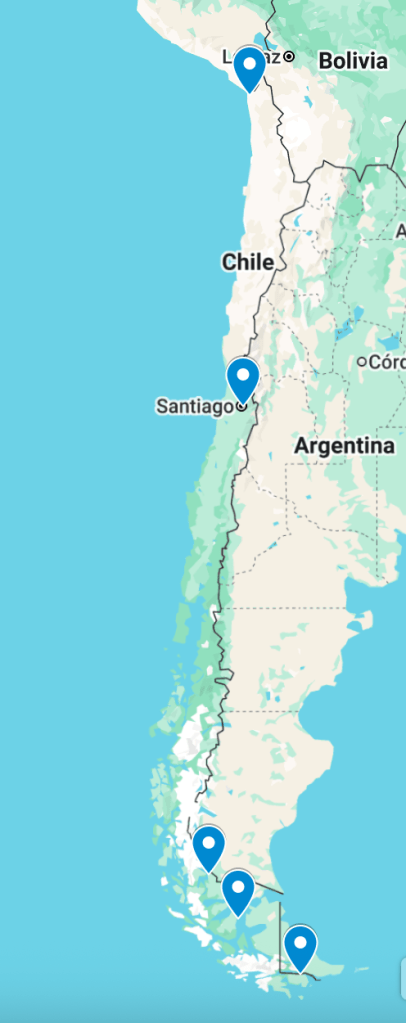

A different way of understanding is to travel from one end of Chile to the other. Living, as I do, in the Falklands, my point of entry to Chile is Punta Arenas, which is pretty far south but not quite the most southerly city in Chile – that honour goes to Puerto Williams, a further 186 miles away on the island of Navarino.

If you started your journey from Puerto Williams and flew north to Arica, the final city in northern Chile, you would be flying for 7 hours to cover 2,579 miles and you’d have to change planes twice – in Punta Arenas and in Santiago. That’s a lot of flying and a lot of distance. As a comparison, if you left the UK from Heathrow and flew south, the same flight distance would get you to Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso.

Chile is a very long country.

It’s also a very, very thin country – at its narrowest point near Puerto Natales in the South, it is only about 10 miles wide, if you measure from the sea to the frontier with Argentina. At its very widest (near Antofagasta in the north) it is around 200 miles wide – or Southampton to Leeds. Not very wide at all…. The reason it’s so thin is the Andes mountain range, which is a substantial eastern border naturally limiting the width of the country.

Chile’s shape has changed a little since it became an independent state, the main effect has been to make it longer. The War of the Pacific in 1879 to 1884 between Peru, Bolivia and Chile resulted in Chile gaining substantial territory in the north, full of rich mineral resources. Bolivia lost its Pacific coastline and became landlocked. This loss is still raw in Bolivia – they maintain a navy (on Lake Titicaca) and across Bolivia you see slogans on buildings claiming “Mar para Bolivia” (Sea for Bolivia), asserting their right to their old coastline. In reality there seems little chance of the current borders changing.

The major effect of all that length for Chile is some very different climates and eco-systems, but that’s a post for another day.